Opinion - March 22, 2020

A crisis we accept is an adventure

Written by Bertrand Piccard 5 min read

What are we going to do about the current crisis? Will we suffer from it or learn from it?

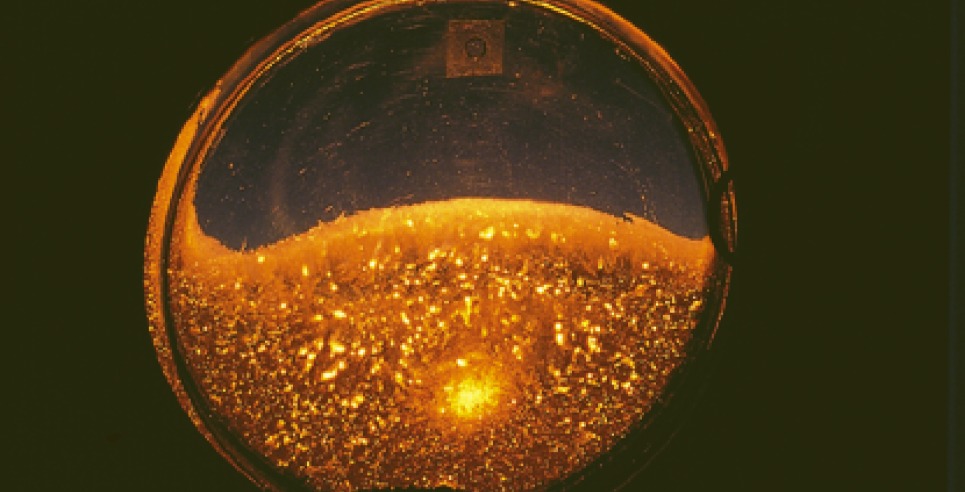

In the midst of the coronavirus crisis, I brought out this photo taken at the end of my round-the-world balloon trip. It shows a window of the Breitling Orbiter 3 capsule on which the humidity of the night deposited large ice crystals. What's on the other side? A beautiful sunrise. But to see it, you'd have to go through the ice first.

That's what we fear in times of crisis. When there is too much ice, problems, anxieties, we often prefer to suffer in the ice we know, rather than take the risk of trying to see what is on the other side.

Why is that? Because, prisoners of our habits and certainties, we find it difficult to see the world other than through the filter we have built. So we hate crises because they brutally take us out of the automatisms in which we sleep.

So how do we react? We can tell ourselves that the crisis is there to destroy us and we will suffer all the more, cut off from a broader understanding. On the contrary, we can decide that life forcefully forces us to question ourselves, to disconnect the autopilot, to stimulate us to take our destiny in hand more consciously. We do not have the choice of what life brings us, but we do have the choice of what to do with it. The crisis that we accept becomes an adventure, with its share of unexpected events, twists, emotions and teachings; the adventure that we refuse will remain, conversely, a crisis, with a surplus of suffering and despair.

Does the experience of a crisis really depend on the decision we make? I think it does. Of course, we would prefer to remain in the comfort of our daily lives, and I am not saying that we should rejoice when a crisis erupts. But when we are faced with it, we have to do something about it. That is why these days I often repeat the words of the Stoic philosophers:

"Give me the strength to change what I can change, the courage to endure what I cannot change, and the wisdom to distinguish one from the other."

So today there is no more room for fatalism than for stress. Fatalism consists in accepting what one could change, without fighting to avoid it. Stress, on the other hand, occurs when we exhaust ourselves trying to change what we cannot change. Mourning the past, recovering from losing what we loved, is an active decision to accept the irreversible. It is not fatalism.

In this sense, we cannot, of course, change the current epidemic, but we can change ourselves.

We are being carried towards the unknown by the "winds of life", by everything that is beyond our control and will, like a balloon pushed by jet streams. We will not be able to change our trajectory as long as we remain at the same altitude. The first thing we learn about flying a balloon is that the atmosphere is made up of very different layers of weather, all of which have a different direction and speed.

So you have to change altitude to change direction, and to do that you have to drop ballast.

In the winds of life, it's the same thing: we must learn to change altitude, psychologically, philosophically and spiritually, to open ourselves to other visions of the world, to find currents, influences, solutions, which will offer us better directions. The ballast that we will have to let go in order to climb is paradoxically made up of what we have falsely learned to keep: our certainties, habits, prejudices, beliefs, convictions, dogmas and other paradigms.

To bear fruit from a crisis therefore begins by considering the opposite of what we have learned to do and think, in our responses, reactions and decisions. We get rid of our automatisms to become aware that we are at a determining moment of our existence and that everything will be played out according to our way, old or new, of understanding life. To become more creative, more open to other ways of thinking, and in this sense open to others, to ourselves, to life. We need to put the important values of existence back at the centre of our priorities. The crisis must allow us to be better after than before. Otherwise it will be useless.

If we look at the way our world works, which has been so badly damaged by the coronavirus epidemic, what ballast do we need to get rid of? A globalized interdependence that allows an epidemic to spread in a matter of weeks through excessive transport, a culture of waste that makes us forget respect, a frantic pursuit of short-term profit at the expense of sustainability, a destruction of human and natural capital, with the result that we have no time to waste.

And in our everyday life? A very materialistic attachment to life, focused on quantity and possession rather than quality and solidarity; on having at the expense of being; on the search for immediate pleasure that makes us forget the essential. What if that's the ballast that we have to go overboard? To find, at another altitude, a new direction made up of spiritual values of kindness, wisdom and compassion. To gain a little humanity in a world that is degenerating, wouldn't a crisis even become desirable?

Whatever we learn from it, it is clear that we are suffering from it. Through deaths, losses, disillusionment, anguish. Would not the ultimate altitude consist then in admitting that we do not know the true meaning of our passage on Earth and that this period of confinement can be an opportunity to seek it within us, in silence, sheltered from the deafening effervescence of the usual routine?

Written by Bertrand Piccard on March 22, 2020